Silver Springback

I have an occasionally-alarming tendency to find a passing reference to something, usually historical, and be unable to resist digging and digging and digging to find out more about it, sometimes just because of the mystery I projected on it initially. This almost always occurs when I'm trying to research something else which is much more pressing, and no, I don't remember what it was that led me here.

So it was with the springback book; I found some brief mention of it when looking into lay-flat binding methods, because my interest in bookbinding began chiefly for the purpose of notebooks, for which I have the standard artist's fetish, and pages refusing to lay flat is a great reason to never use a particular notebook again. I don't recall which of the myriad articles I've read on the subject by this point was the first, but it referred to the springback as a construction method suited to books that have to spend a lot of time opened, and breezed past the reference so casually that I had to look into it - only to discover that it was terribly difficult to find information on. That, as I eventually found out, is because the method was principally used in Germany to produce account books and fell out of common use sometime in the 19th and 20th centuries for obvious technological reasons. It is largely irrelevant to today's market, so few people are preserving it in an already-small field; due to its origins, an awful lot of the material I could find was in German, and the rest tended to be incomplete or otherwise incomprehensible.

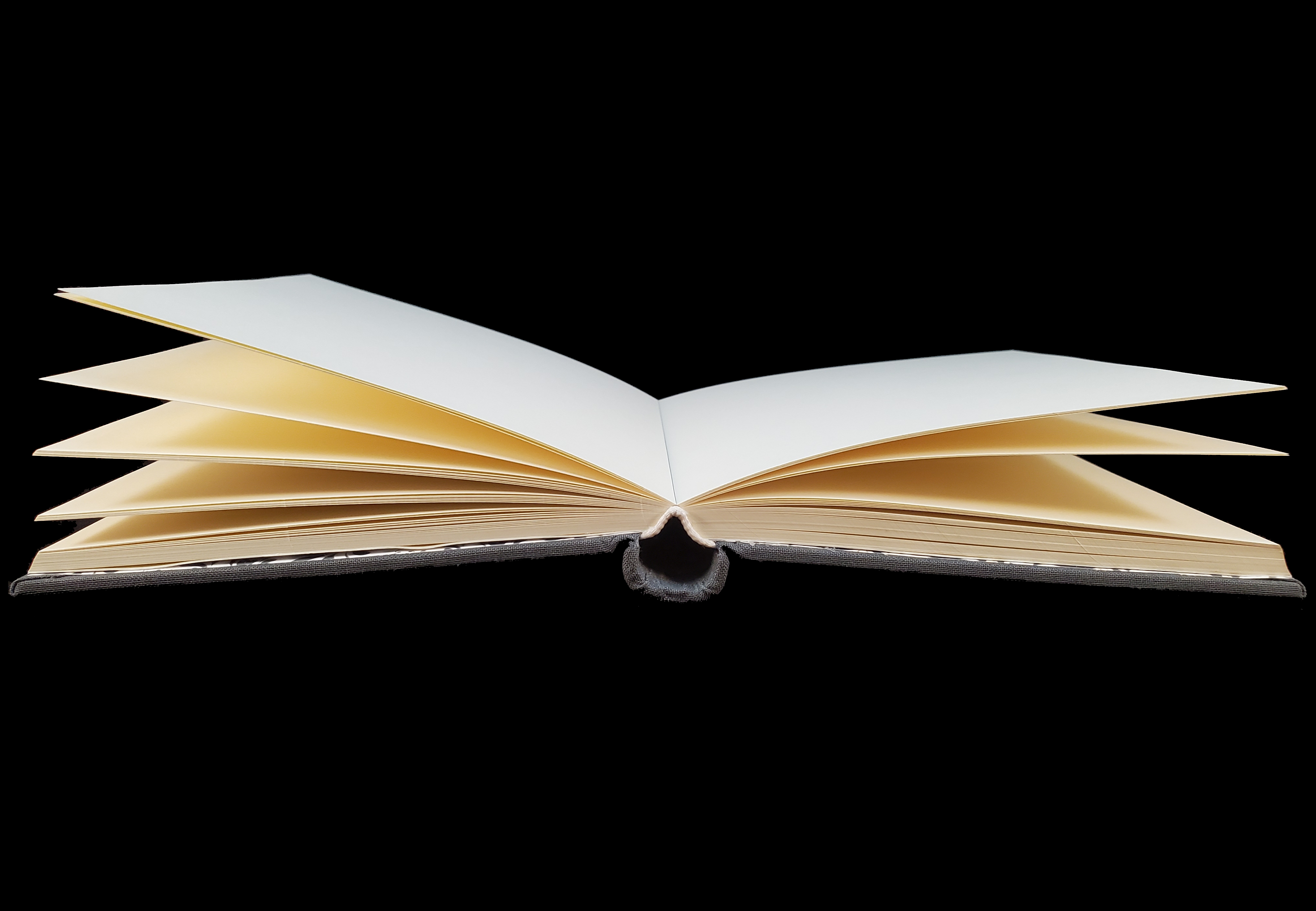

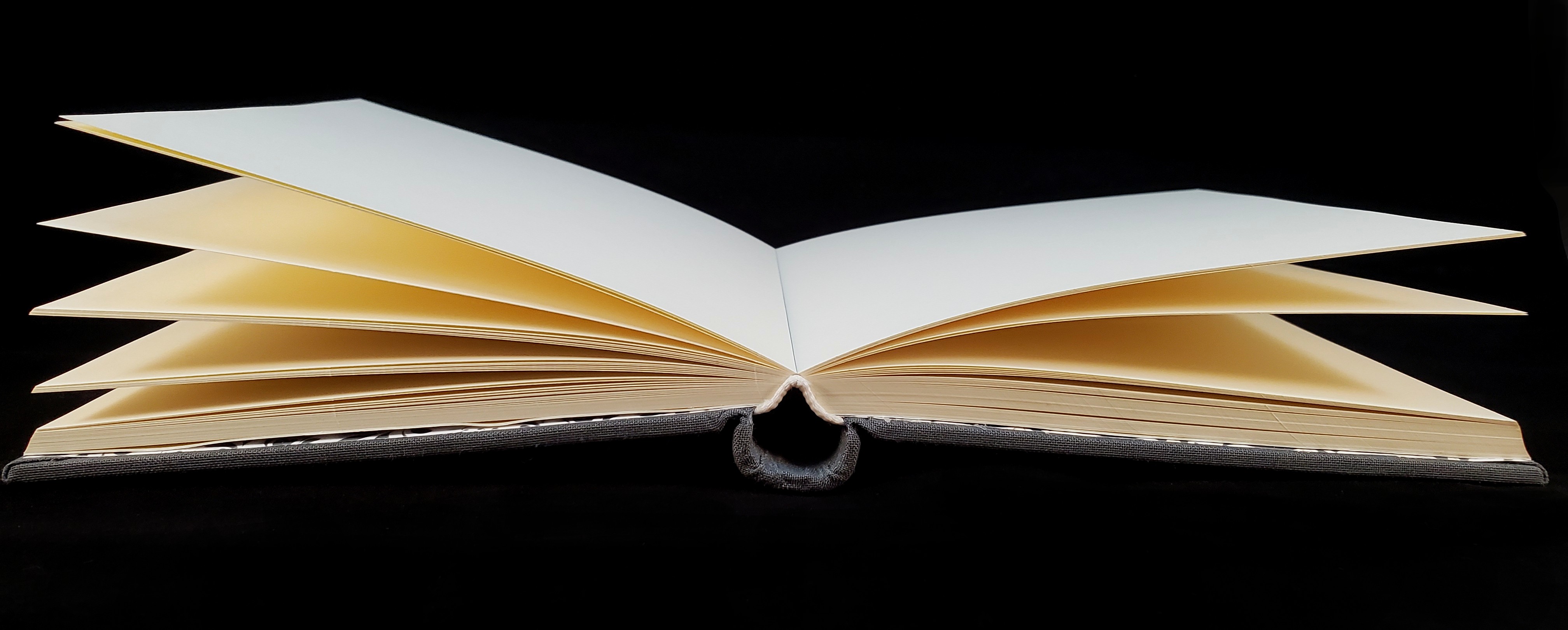

I eventually cobbled together enough information to work with. I'm sure my version falls somewhat short of a pristine historical reproduction, but it works as intended and reflects a wonderful tidbit of historic ingenuity. The round spine is a thick, layered assembly of paper and cloth, such that it can flex a bit but remembers its shape, so that as the book is opened, the spine of the pages - which is rounded like traditional books often are - moves away from the spine proper and flexes the spine out; past a certain point, the spine overcomes the pressure exerted on it (hence the "spring" descriptor) by the page block which then collapses away from the spine, and the book is left laying open, flat as could be.

It's that opening mechanism that intrigued me because it's so difficult to describe. I couldn't quite grasp it when I was reading about it myself, and now I fear I'm failing to explain it satisfactorily, because it's so easy to be distracted by certain exciting details of its engineering and end up abandoning the explaining for the mechanical reverie. It's clear enough to me now, looking at the photos on this page of the book closed and open where the end of the spine is fully visible, but it's a joy to feel the spring in action that I regrettably can't fully convey here.

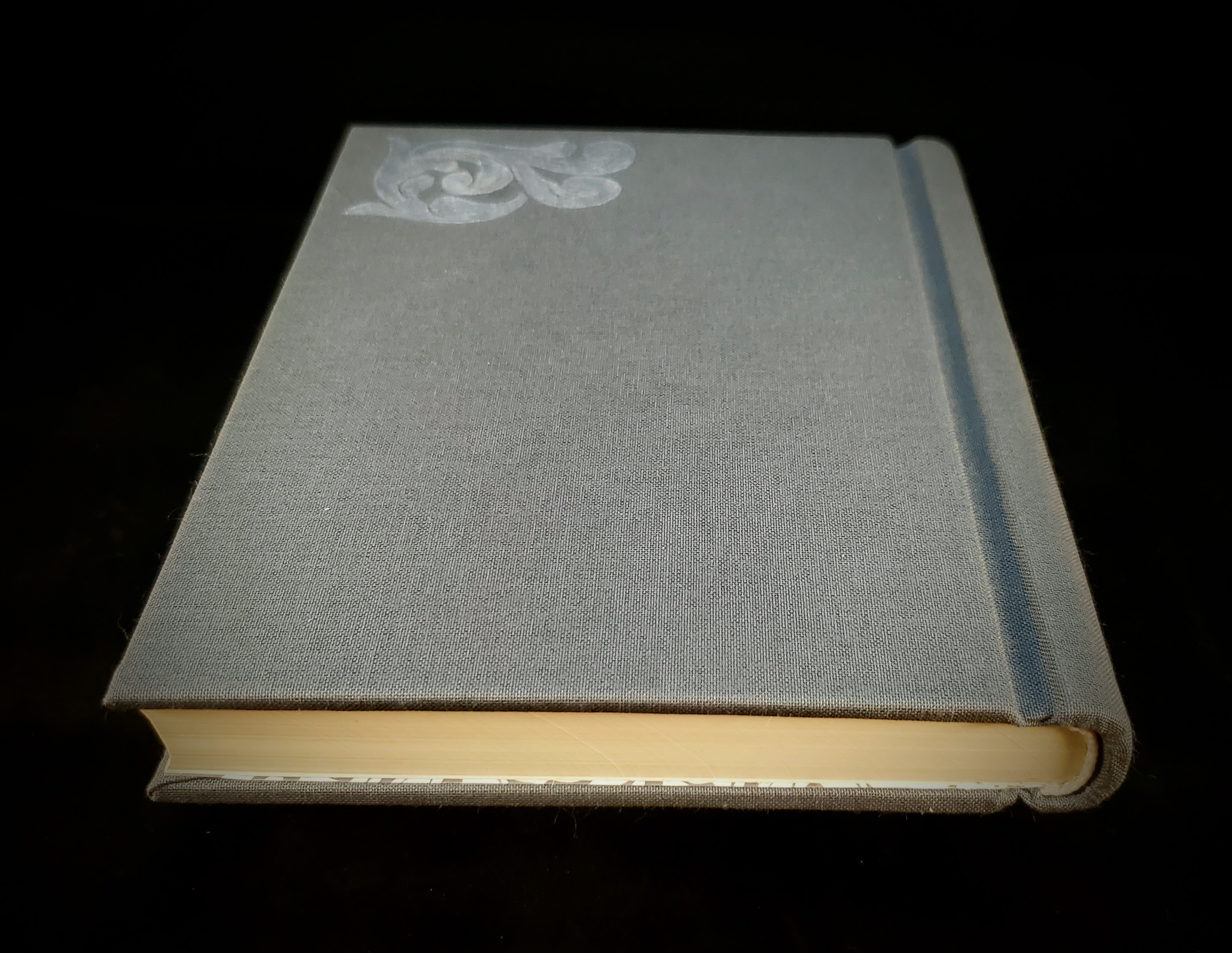

A view of the book when closed - note the page block laying all the way back against the spine

A view of the book when open - note the spine of the page block fully separated from the spine of the cover

I've mentioned in a few other pages my penchant for simple decoration. When working on this book, I couldn't help feeling that this one needed something a little more ornate, but I couldn't go full-on Rococo with it, if only because I'm fresh out of stucco. But this suddenly struck me as a wonderful opportunity to pay homage to the traditional leathercraft aesthetic that I'd eschewed when actually working in leather - the forms seen in leather tooling are beautiful, flowing, and intricate, a perfect match for what this project seemed to deserve, but by the very nature of the context entirely separate from the fusty Old West connotations that kept me from using them in leather. It was distanced even further when I saw a roll of matte silver foil next to some grey bookcloth - neutral colors to offset the complex decor and mechanism. I did give in a bit, though, with the endpapers; I had brought some offset printed sheets home from work (they were overs, don't worry) with a lovely grey leafy-vine motif. This matched the plant-inspired imagery of the foil and the other colors involved perfectly. It all came together in the end.